Here Is Why AI Could Very Well Be a Giant Bubble

Economists do have something to say about AI...

Arguments against a bubble often cite current utilization, noting there are no idle GPUs—unlike the dark fiber excess during the late 1990s telecom build-out—and arguing that there is currently not enough AI infrastructure to meet potential demand.

A key concern suggesting a bubble is that the massive CapEx buildout requires very rapid scaling of demand, yet much of the current use of AI services is free, generating no revenue. For instance, only just over 1% of Microsoft’s Office 365 subscribers pay for Microsoft 365 Copilot.

The driving force—the race to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—is highly speculative. Evidence suggests that LLMs, which are built on sophisticated pattern-matching rather than robust world models, are reaching rapidly diminishing returns in scaling and failing to deliver on the AGI promise.

Multiple potential developments could limit the need for vast cloud computing, including the shift of inference processing to the edge, the use of smaller, domain-specific models, and dramatic improvements in chip and model architecture that reduce resource needs.

The financial profile of big tech companies is shifting from asset-light to asset-heavy business models, with capital intensity approaching that of utilities. This heavy CapEx spending is causing free cash flow to stall or decline, even as net income grows.

Financial viability is questioned because the rapid depreciation of AI chips (obsolete in 3 to 5 years) leads to estimates that annual depreciation might be double the revenue generated by new AI data centers.

For economists, the abundance of LLMs with little to distinguish them suggests that once the current scarcity in GPU capacity ends, the market will look like a commodity market with little pricing power.

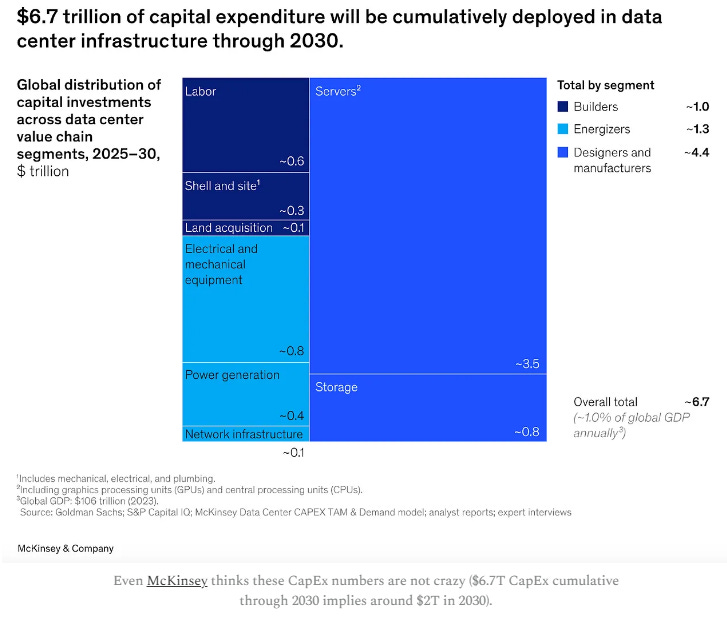

Collectively, the phenomenal build-out might be highly irrational, as individual players race to AGI (a prisoner’s dilemma). For the sums to add up, data centers must generate $2T by 2030, meaning sales have to scale 50x to 100x from current levels.

Is AI a bubble? Nobody really knows, given the epic CapEx build out, it crucially depends on very rapid scaling of demand for AI services. We have heard several arguments from those that argue AI isn’t in a bubble, like:

There are no idle GPUs (like there was dark fiber during the internet/telecom build-out in the late 1990s).

There isn’t enough AI infrastructure

AI can do amazing things we can’t even imagine

We already provided some counterarguments in a previous article, like:

Diminishing returns in scaling LLMs, scaling is ever more expensive and delivers ever fewer improvements.

Shift inference processing to the edge. What if inference (the actual use of AI, as opposed to training) is done mostly on devices, rather than in the cloud?

Possible dramatic improvements in resource efficiency, provided by new model or chip architectures.

Race to AGI, but we might never get there.

No idle GPUs

While CapEx spending accelerates, that doesn’t mean that it will generate a return. As it happens, much of its use is free, not generating any revenue (let alone a return) at all.

It’s not difficult to keep these GPUs humming if you give away the services. For instance, just over 1% of the 440M subscribers of Microsoft’s Office 365 actually pay for Microsoft 365 Copilot, and keep in mind that Microsoft:

has one of the largest commercial software empires in history, thousands (if not tens of thousands) of salespeople, and thousands of companies that literally sell Microsoft services for a living.

Possible breakthroughs

While Nvidia chips currently dominate the market and are expected to continue doing so for the foreseeable future (we explained the reasons in previous articles, here and here), the export restrictions to China have spurred the Chinese to develop their own.

Given the huge number of engineers the Chinese education system produces every year, its sophisticated supply chain and manufacturing base, and a determined government willing to spend what it takes, you have a recipe for rapid innovation.

Today’s chips from the likes of Huawei are no match for the most advanced ones from Nvidia (Blackwell), but a main reason is that China doesn’t have access to ASML’s EUV machines.

There are more fundamental developments underway (not just in China) in photonics (Nvidia is one of the companies developing hybrid chips) and analog chips, and maybe even quantum computers (although these are more complementary than substitutes as they are ill-equipped for the type of massive parallel processing that GPUs do).

Not ready for the limelight yet, but these could potentially produce orders of magnitude breakthroughs.

So we have multiple potential developments that could potentially limit the need for AI cloud computing:

The shift to edge computing (inference).

The need for smaller, more domain-specific models built on domain-specific data that tends to hallucinate less.

Improvements in LLM architecture that dramatically reduce resource needs.

Dramatic improvements in chip design, enabling a step increase in compute.

With respect to model architecture, there are certainly many alternative paths to brute scaling. The Chinese went this way as they are resource-constrained, leading to more efficient models like DeepSeek and recently introduced models like SpikingBrain and Kimi K2, or a model developed in Singapore by Sapient Technology.

We’re not saying any of this will happen (although the first two are already happening), and we acknowledge the possibility that even if it does, this could be filled with additional demand from yet unknown applications (certainly there will be some of that), but the potential is there.

AI can do fantastic things

AI is already capable, and surely companies will invent a myriad of new ways to use it, especially as it keeps improving. But consider this:

Reflecting upon the internet bubble with the benefit of hindsight, whoever was the most bullish about the internet in the year 2000 was still not bullish enough. At the turn of the century, we had no smart phones, no tablets, no Wi-Fi, no Google, no Facebook, no TikTok, no cloud, and no video streaming. The internet has become much more important than even the biggest optimists believed.

Bottlenecks

We also mentioned bottlenecks, mainly in energy but also in skilled personnel and other issues, but these might actually keep the build-out in check.

Economists might have something to say

Do the sums add up?

Market characteristics

Business models (asset-light to asset-heavy)

History of mania

The race to AGI

Here is one reason why economists might have a leg up on industry specialists: seeing the forest through the trees and recognizing a prisoner’s dilemma. There are two reasons why the current phenomenal build-out of AI data centers might be optimal for individual players, but sub-optimal collectively:

The big tech CEOs want to get first to AGI

US players want to get to AGI before the Chinese get there

Given the size of the price (AGI), each player individually has an incentive to rapidly scale up, but collectively this could very well produce huge excess capacity.

But whether LLMs will reach AGI anytime soon is still very speculative. Dutch economist Servaas Storm from the Department Economics of Technology and Innovation (ETI) at Delft Technical University argues that we are reaching peak GenAI and “evidence is piling up that GenAI is failing to deliver.”

He bases his view on an impressive amount of studies, and the main point is that scaling isn’t going to lead to AGI, as:

LLMs are not constructed on proper and robust world models, but instead are built to autocomplete, based on sophisticated pattern-matching

Indeed:

even when trained on all of physics, LLMs fail to uncover even the existing generalized and universal physical principles underlying their training data. Specifically, Keyon Vafa, Peter Chang, Ashesh Rambachan and Sendhil Mullainathan (2025) note that LLMs that follow a “Kepler-esque” approach, can successfully predict the next position in a planet’s orbit, but fail to find the underlying explanation of Newton’s Law of Gravity (see here). Instead, they resort to fitting made-up rules, that allow them to successfully predict the planet’s next orbital position, but these models fail to find the force vector at the heart of Newton’s insight.

He cites multiple studies by industry experts reaching similar conclusions, and there is considerable empirical evidence that shows that scaling is already producing rapidly diminishing returns.

This is pretty concerning because the whole race towards AGI is based on scaling; it’s the driving force behind the multiple trillion-dollar AI data center buildout.

Some of the people involved, like Google’s Eric Schmidt, are starting to recognize this, and he urged Silicon Valley to

stop fixating on AGI, warning that the obsession distracts from building useful technology.

By the way, if AI turns out to be a bubble and we’re much further from AGI than Silicon Valley thinks, what lasting value gets built? You could tell a story about how the dot-com bubble paved the way for all the value the internet has generated. What’s the equivalent for this AI buildout?

The GPUs—70% of capex—are worthless after 3 years. The buildings and power infrastructure last decades but are overbuilt for non-AI workloads. Perhaps the enduring value is this new industrial capability: the ability to rapidly manufacture and deploy massive compute infrastructure on demand.

Business use

We’re not too worried by the now-famous MIT study, which showed that 95% of enterprise use of GenAI is failing to raise revenue growth, although the reason for this, as reported by Fortune:

generic tools like ChatGPT [….] stall in enterprise use since they don’t learn from or adapt to workflows

We’re not worried because all new technology goes through a kind of J-curve effect as organizations learn how to make the best use of these. That takes time. However, we must say that this lack of learning and adaptation to workflows is concerning.

There are multiple examples of companies rolling back AI pilots and rehiring the employees they were supposed to replace, according to Servaas Storm (see link above), as well as much of the demand (Greenlight Capital):

Rather than external enterprises or consumers spending new money, much of the AI revenue comes simply from AI companies buying products and services from each other. The largest announced third-party deal is KPMG’s annualized $400 million spend with Microsoft, which includes cloud services that might not be entirely AI related. In the context of this discussion, $400 million is but a pittance.

This is a primary reason why we’re examining companies that offer solutions to help organizations maximize the use of AI, such as BOX (see our recent primer). We also believe that enterprise will primarily resort to smaller, more domain-specific models trained on domain-specific data that do not necessarily run in the cloud.

Industry characteristics

Economists also have something to say about the industry characteristics and likely profitability of players. At present, there is a scarcity in GPU capacity, which props up pricing.

But this can easily flip, which would be a dangerous thing, as there are many LLMs and there is little to distinguish one from the other, so for economists, this looks like a commodity market where players have little pricing power.

Even a casual glance bears this out. Much of the use is free, with few consumers willing to pay for AI. There are many free open source models one can host on one’s own facilities (and even adapt to particular needs), and these are not necessarily worse than the huge models from the big hyperscalers, (VentureBeat, our emphasis):

The Chinese AI startup Moonshot AI’s new Kimi K2 Thinking model, released today, has vaulted past both proprietary and open-weight competitors to claim the top position in reasoning, coding, and agentic-tool benchmarks.

Despite being fully open-source, the model now outperforms OpenAI’s GPT-5, Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4.5 (Thinking mode), and xAI’s Grok-4 on several standard evaluations — an inflection point for the competitiveness of open AI systems.

Developers can access the model via platform.moonshot.ai and kimi.com; weights and code are hosted on Hugging Face. The open release includes APIs for chat, reasoning, and multi-tool workflows… Moonshot AI has formally released Kimi K2 Thinking under a Modified MIT License on Hugging Face. The license grants full commercial and derivative rights

We featured a small model developed in Singapore before, one which dramatically cuts resource use (by 100x) without much, if any, performance compromises.

Business model

Morgan Stanley estimated global spending on datacenters to be $3T between now and 2028 with $1.4T covered by the cash flow of US big tech, and much of the rest:

That means $1.5tn needs to be covered from other sources such as private credit – a growing part of the shadow banking sector that is raising the alarm at the Bank of England and elsewhere. Morgan Stanley believes private credit could plug more than half of the funding gap. Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta has tapped the private credit market for $29bn of financing for a datacentre expansion in Louisiana.

McKinsey & Company estimates cumulative total spending of $6.7T on data centers globally through 2030, including $5.2T in capital expenditures on those equipped to handle AI processing. That’s a lot of money, which has to generate a return at some point.

And there are two additional features of the business model generating additional concerns:

From capital-light to capital-heavy

Rapid depreciation

Asset-heavy business models

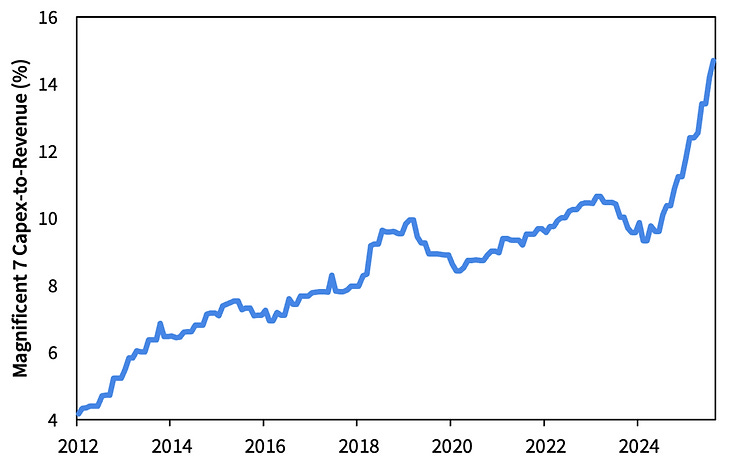

AI-server farms are a particularly capital-intensive business model, so these big tech companies are shifting from an asset-light to an asset-heavy business model (Sparkeline Capital, our emphasis):

The Magnificent 7’s capital intensity is quickly approaching that of utilities, the most asset-heavy sector. As the next exhibit shows, Meta, Microsoft, and Alphabet are each set to spend between 21 and 35% of their revenue on capex, more than both the average global utility today and AT&T at the height of the telecom bubble.

While their asset-light businesses keep on generating lots of profits and cash, the heavy CapEx required for AI servers is eating into that cash. While profits are still growing rapidly for the big tech companies involved in the epic AI-server build-out, cash flow is stalling or declining.

The profit growth is also masking their AI-business performance, which isn’t split out. It looks like all is well, but the stalling cash flow is an ominous sign (WSJ, our emphasis):

From 2016 through 2023, free cash flow and net earnings of Alphabet, Amazon, Meta and Microsoft grew roughly in tandem. But since 2023, the two have diverged. The four companies’ combined net income is up 73%, to $91 billion, in the second quarter from two years earlier, while free cash flow is down 30% to $40 billion, according to FactSet data.

Free cash flow isn’t enough anymore, even for big tech (Spectramarkets):

And you can also add the fact that AI spending is no longer coming out of free cash flow. Oracle, META, and others are doing massive bond issuance to fund the splurge.

A particular worry is that an increasing amount of financing is done by private equity, but this is stuff for another day.

Answers from CEOs aren’t entirely reassuring either:

The issue now is that the market is finally asking questions about AI payback and the answers are not at all convincing. Sam Altman, when asked about how he could possibly justify a $1.1T spend on just $20B of revenue, basically told the interviewer to pound sand and for investors to eff off and short the imaginary stock of OpenAI if they don’t like the vision.

The companies involved seem to realize revenues (let alone cash flow) aren’t rising anywhere near to pay for the CapEx and are throwing new business models out, from browsers to turning to the advertisement business on AI-created slop.

Deutsche Bank reported that spending on ChatGPT in Europe has stalled since May. Given that revenues have to scale rapidly to make the business model viable, stalling growth this early in the ramp-up is a particularly bad omen.

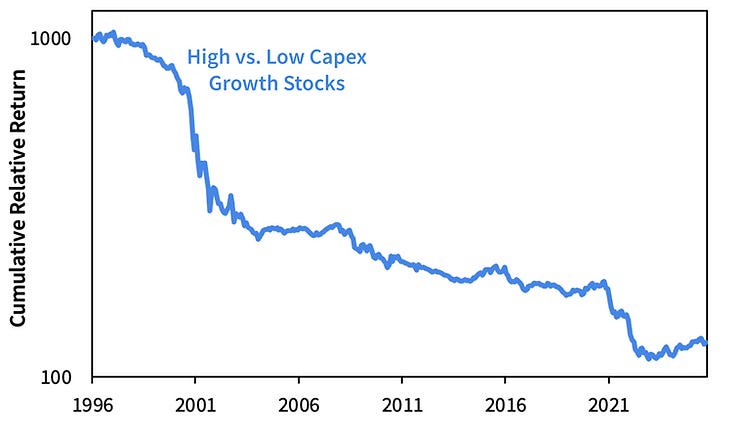

CapEx-heavy firms tend to underperform

From Sparkeline Capital:

Since 1963, companies that aggressively grew their balance sheets underperformed their more conservative peers by a considerable -8.4% per year. This so-called “asset-growth anomaly” is actually widely studied in the academic finance literature. The illustrious Fama and French even included it as a distinct factor in their five-factor model, alongside the market, size, value, and profitability factors… As the next exhibit shows, firms rapidly increasing capital expenditures have also underperformed their more conservative peers.

Rapid depreciation

Then there is the rapid depreciation, from Preatorian Capital (our emphasis):

I’m assuming that the building depreciates over 30 years, the chips are obsolete in 3 to 5 years, and then the other stuff lasts about 10 years on average. Call it a 10-year depreciation curve on average for an AI datacenter. Which leads you to the first shocking revelation; the AI datacenters to be built in 2025 will suffer $40 billion of annual depreciation, while generating somewhere between $15 and $20 billion of revenue. The depreciation is literally twice what the revenue is.

History of mania

What seems rational for individual firms (racing CapEx buildout) might very well be highly irrational collectively. This is what is happening in the Chinese EV market, where there are dozens of firms producing EVs, creating excess capacity even in the face of rapidly rising demand.

Historical capital expenditure booms have typically resulted in overinvestment, excess competition, and poor stock returns.

This time isn’t likely to be different, especially as the Big Tech CEOs feel they are in an AI race they can’t afford to lose, that whoever wins the AI race and gets first to AGI wins “all markets” (as supposedly AGI will solve all problems). The involvement of some big egos only exacerbates this dynamic.

Do the sums add up?

No, at least not yet. Bain & Company calculated that in order to be viable, new data centers have to generate $2T by 2030, while they have generated only some $20B to $40B to date. Basically, they have to scale up sales 50x-100x.

Bottlenecks

We might be saved from some of the excesses by a shortage in energy, which is already keeping some capacity idle. and there are other bottlenecks as well:

For you to deploy $2 trillion of AI CapEx a year, someone else needs to be producing $2 trillion worth of all the other datacenter components, not just the chips. The people upstream to the datacenters - the companies producing everything from copper wire to turbines to transformers and switchgear - would need to build more factories. The problem is that those factories have to be amortized over a many decade lifespan. At usual margins, those factories are only worth building if this AI demand lasts for 10-30 years. The companies building those factories are not AGI pilled - they’re decades old industrials running low margin businesses which have been burned by many previous swings in demand.

Conclusion

We are not ready to call the AI datacenter build-out a bubble, as we don’t know how demand is going to evolve, and there are those, like Goldman Sachs, arguing it’s not a bubble.

However, what is clear is that we have very capital-intensive businesses with rapidly depreciating assets, with little pricing power and an uncertain outlook on whether their products can generate the rapidly rising demand that will enable them to make the sums add up. It’s possible, but demand has to rise exponentially for the sums to add up.

And there is always the possibility for innovations to dramatically cut the resource needs to train and/or run the models powering AI.

So, while we don’t think anyone can determine with any kind of certainty whether this is a bubble or not, we do think the scale of the build-out is highly speculative, which makes us a little wary to invest in some of these companies at this stage.

What’s also clear is that in case this does turn out to be a bubble, the fallout of the bursting of the bubble will be particularly nasty and have wide ramifications for the economy and the markets, in part the result of how much of it is financed (private equity), but that’s a matter for another day.

From a trusted source: [Have been traveling China on leisure for the past two weeks and spent Thanksgiving with an eclectic group including a Chinese VC with a full-stack AI focus. The chip and energy consumption limitations on GPU have really steered focus and investment towards more efficient models, with much discussion around Moonshot AI's Kimi and low training requirements (and at a cost of less than $5M). There are some coherence issues, but they see models improving to the point where edge computing dominates with LLM-capable (client-based) PCs about 12-18 months away. Naturally, this led to a discussion about infrastructure investment and comparisons to all the fiber laid but never lit up in the late 90s/early 2000s. They are seeing investment shift more and more towards vertically-focused agentic solutions.]

One should also check China's progress in photonics:

[The chip war situation has developed not necessarily to America’s advantage. China’s 14th Five-Year Plan $15B quantum push has produced millions of photonic quantum chips that are now solving problems in hospitals and laboratories, but using 10% of the power used by an electronic chip and running 1000x times faster. For the first time, optical quantum computers are industrial-grade products.]

https://herecomeschina.substack.com/p/chinas-photonic-chips-end-americas?r=16k

From the horse's mouth: [The head of Google’s parent company has said people should not “blindly trust” everything artificial intelligence tools tell them. In an interview with the BBC, Sundar Pichai, the chief executive of Alphabet, said AI models were “prone to errors” and urged people to use them alongside other tools. In the same interview, Pichai warned that no company would be immune if the AI bubble burst.]

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/nov/18/alphabet-boss-sundar-pichai-ai-artificial-intelligence-trust